Creative Problem Solving

If you would like to incorporate activities addressing this competency into your class, please click V-module Competency #2: Creative Problem Solving!

Definition and Learning Models

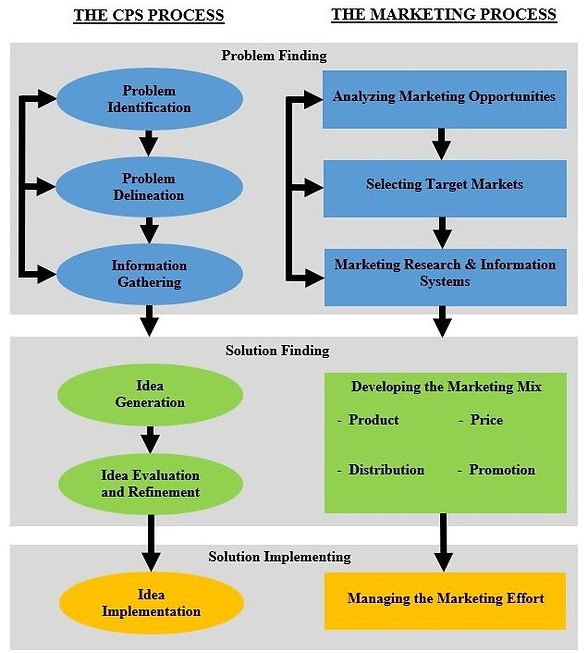

In the past, creativity has been considered a personality trait. However, more recent research views the concept through a multidimensional lens. Hung (2015) reviewed many definitions of creativity and identified the common elements among the definitions as: “(1) new, original, novel (2) ideas or insights that occur in the process of (3) problem solving and produce a product that is (4) useful and accepted in its social/cultural community” (p. 238). Thus, problem-solving has been recognized as a significant aspect of creativity. Hung (2015) suggested problem-based learning (PBL) as a means to provide an environment that fosters creativity. Various PBL models have been used, but the ones that require a high degree of self-directedness and use highly complex problems hold the most promise. Per Hung (2015), PBL is successful in fostering creativity due to the alignment between its instructional support features and the characteristics of creativity. Creative problem solving (CPS) has also been described in the context of marketing. Titus (2000) described marketing as the process of offering creative solutions to consumer problems and emphasized the need to increase students' knowledge of creative problem-solving. CPS is a special case of problem-solving in general. Problem-solving can be classified as algorithmic or heuristic (Amabile, 1983, as cited in Titus, 2000). Algorithmic problems are those for which a known path to a solution exists, like assembling an airplane. Heuristic problems are those that don’t have an easily identifiable path to the solution, like writing a paper. These problems allow for creative expression, and most marketing problems are, by definition, heuristic. Problems like product positioning or marketing communication have no identified path to the solution. Creativity can be thought of as the birth of imaginative new ideas (Miller, 1987, as cited in Titus, 2000). In the context of problem-solving, creative solutions need to be novel and appropriate. Thus, CPS is defined as activities that are undertaken to generate solutions that are 1) novel and appropriate to the task and 2) where the task is heuristic rather than algorithmic. The CPS process is a methodical, sustained, and disciplined cognitive process (rather than freewheeling and unstructured). Various CPS frameworks break down the CPS process into distinct stages that correspond to marketing processes, such as problem-finding and solution implementing (Titus, 2000) (refer to the figure below). Most CPS frameworks recognize the role of divergent and convergent thinking in the CPS process. Divergent thinking is the ability to produce many innovative or unusual ideas to expand the range of possible solutions. Convergent thinking is the ability to converge on the best possible solutions or the ability to evaluate or judge the possible solutions for implementation. There are various analytical techniques to enhance both divergent and convergent thinking.

Figure

Comparing the creative problem-solving (CPS) process and the marketing process

Source. Titus (2000)

Application of CPS in Fashion Pedagogy

Design as Problem Solving

In the fashion industry, new technologies, globalization, and changing consumer preferences have created an unlimited appetite for creativity in products and ideas. Schmidt and Zarestky (2021) suggested that fashion design pedagogy needs to cater to the industry by preparing graduates with adaptive skillsets to engage creatively in all three roles of (1) problem solvers, (2) artists, and (3) design thinkers. Many other educators view the fashion designer as a problem solver and apparel design teaching as a problem-solving activity for solutions to problems of fit, usability, and versatility (Palomo-Lovinski & Faerm, 2009; Ambasz, 1972, as cited in, Schmidt & Zarestky, 2021). Lee (2006) considered problem-solving capability as a key aspect of creativity and explored the role of intuition in the development of creativity. The application of CPS in fashion pedagogy has been reviewed by Oh (2017). The author suggested the Creative Problem-Solving Thinking Skills Model, refined by Puccio et al. (2010), as a comprehensive cognitive and affective model designed to promote creative thinking and generate solutions. The model consists of three stages – clarification, transformation, and implementation – which correspond to the stages in the marketing approach of Titus (2000). Each stage requires a dynamic balance of divergent and convergent thinking.

Testing CPS Models

CPS skills have been tried and tested in fashion pedagogy by Im, Hokanson, and Johnson (2015) with a longitudinal study conducted in a fashion merchandising program in the U.S. A problem-solving skills course was developed, which included activities focused on breaking existing habits and encouraging new behaviors. Students completed 12 activities labeled ‘differents’ throughout the term. These activities were aimed at developing exploration and risk-taking behaviors, such as trying out new food. In-class exercises included attribute listing methods in which students developed lists of alternative uses for common objects. The Torrence Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT), administered pre and post the CPS course, revealed higher scores for creativity after the course. The TTCT was also administered 3 years after completion of the course to reveal that students retained their CPS skills for up to 4 years. Karpova et al. (2011) examined the effect of creativity exercises (but not CPS) on 114 students in an apparel program at a US university. The students completed 12 creative activities (e.g., the bug report) across 4 learning modules over 8-12 weeks. The creativity index in the TTCT was significantly higher in the post-test compared to the pre-test. The authors concluded that creative thinking skills can be improved through creativity exercises. Despite the application of CPS in fashion pedagogy, Oh (2017) suggested some required improvements and concluded that the Creative Problem-Solving Thinking Skills Model has not been fully utilized in apparel education. The author emphasized the difference between teaching creativity and CPS and concluded that previous efforts in applying the model pay more attention to the transformation (idea generation) phase instead of clarification and implementation phases and that fashion-specific CPS techniques need to be developed.

Inquiry-Based Learning (IBL)

Shephard and Pookulangara (2022) used Inquiry-Based Learning (IBL), a pedagogical strategy that involves discovering new causal relationships and solving problems, to integrate slow fashion concepts within the fashion curriculum. Students of fashion courses (that did not contain sustainability concepts) in two different colleges in the U.S. were introduced to slow fashion concepts through the IBL project. The IBL model was taken from Pedaste et al. (2015), which includes five stages: (1) Orientation; (2) Conceptualization; (3) Investigation; (4) Conclusion; and (5) Discussion. These stages can be flexibly applied to build pathways between the inquiry phases. The authors cited various studies on IBL to describe it as a more flexible framework than PBL, as it exposes students to real-world problems. Sustainability and slow fashion concepts were integrated into the course assignments, which were completed throughout the semester, with students completing a submission every 2-3 weeks. Students worked through the IBL process of five stages to investigate brands that apply slow fashion practices (Shepard & Pookulangara, 2022). To assess the effectiveness of the IBL project, students from both classes completed a questionnaire with five open-ended questions at the end of the project. The thematic analysis revealed that the project helped students develop skills in problem solving, communication and critical thinking. Shephard and Pookulangara (2022) concluded that IBL is an effective tool to incorporate slow fashion concepts into courses that do not contain sustainability within the course learning objectives. IBL is a less restrictive tool than other PBL tools but still provides structure and guidance to implement a project, which can be adapted to the needs of the course. The authors posited that IBL can be adapted in courses using various instructional strategies, such as case studies, design and patternmaking labs, and field study.

Classroom CPS Techniques

Titus (2000) discussed the classroom applications of the CPS process and suggested techniques and exercises that can be incorporated into basic marketing courses. For the problem identification stage, the author suggested the ‘bug list’ technique, a fault-finding approach in which students list the things that irritate them about a product (or a service or a location). This technique is best employed in a product or service marketing or retailing course. Below is a bug list for an object (umbrella) prepared by students as a CPS exercise (Titus, 2000). - Bug List Technique (Umbrella Problem) - Design makes it difficult to handle the wind. - Takes too long to dry out. - Doesn’t fit easily into a backpack. - Hard to wrap up after use. - Hard to place in carrying case. - No place to store after use. - Blocks view of others. - Pinches finger when opening and closing. - J-shaped handle is awkward to hold. - Support bars break. - Fabric tears around support bars. - Easy to misplace or forget. - Only one person can fit underneath. - Shape makes it difficult to see where you are going. - Drips on your backpack. - Hard to use in a crowd. - Support bars may poke others. - Doesn’t match attire. - Hard to get in and out of the car. - They’re ugly. - Can be difficult to open and close. - Makes it difficult to carry objects/boxes. - Lower body still gets wet. - Can’t move quickly. - Closing snaps often malfunction. - Automatic open button breaks easily. - Eliminates the use of one hand. For the problem delineation stage, Titus (2000) suggested the progressive abstraction technique, which is a variation of the ‘why?’ method. The process begins with an initial problem – for example, the umbrella design makes it difficult to handle in windy conditions - and progresses by exploring the consequences of not resolving that problem (the person's arm will fatigue and they will get wet, leading them to seek out substitute products.). It is designed to expand the scope of the problem by redefining it to higher levels of abstraction. For the information-gathering process, the Japanese technique of Lotus Blossom was suggested, designed to systematically identify and list all the assumptions about the problem. For the idea generation stage, Titus (2000) used the ‘radial diagram’ technique as it is a powerful free-association technique that proceeds by categorizing and graphically mapping out related ideas and solutions as they are generated, much like a structured version of the traditional brainstorming approach. It helps to identify the usefulness of even the most outlandish ideas generated. Attribute rearrangement is another suggested technique for idea generation, while reverse brainstorming is suggested as a technique for idea evaluation. Thus, Titus (2000) demonstrated flexible CPS techniques that can be used to improve students' divergent thinking during varying parts of the CPS process and can be employed in a product development or retail marketing course. Using CPS as a guiding framework, Lee and Hoffman (2014) suggested the incorporation of active learning techniques. They combine CPS and active learning to introduce an innovative marketing activity called ‘Iron Inventor,’ which is an active learning exercise that takes students through the step-by-step processes of inventing a new product and exposes them to the challenges associated with new product development processes. The activity takes about 120 minutes, can be spread over two class sessions, and is inspired by the popular television show Iron Chef, in which participants combine ingredients to create a novel dish. The effectiveness of this technique was assessed by querying 79 undergraduate marketing students through a 10-question survey. The students reported higher satisfaction with this method compared to a traditional case-based study method. Specifically, the ‘Iron Inventor’ activity increased students’ creative input, enhanced their topic knowledge, and fostered engaged participation.

Summary

In recent research, creativity has been understood as a means to provide creative solutions, not simply the generation of new ideas. Various pedagogical models to enhance problem-solving skills have been introduced in marketing classrooms. PBL, CPS, and Iron Inventor are some of these pedagogical tools. Titus' (2000) comparison of the process of marketing and developing CPS, with the similarity in stages and the utilization of divergent and convergent thinking, is especially informative of the general frameworks of CPS models. The fashion designer is inherently seen as a problem-solver. Thus, the application of CPS models in fashion classrooms would be intuitive. However, existing research shows that work needs to be done on modifying the models for apparel-related pedagogy. Deploying the IBL project by Shephard and Pookulangara (2022) and using the Creative Problem-Solving Thinking Skills Model, as suggested by Oh (2017), are positive steps in that direction.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(2), 357.

Hung, W. (2015). Cultivating creative problem solvers: The PBL style. Asia Pacific Education Review, 16, 237-246.

Im, H., Hokanson, B., & Johnson, K. K. (2015). Teaching creative thinking skills: A longitudinal study. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 33(2), 129-142.

Karpova, E., Marcketti, S. B., & Barker, J. (2011). The efficacy of teaching creativity: Assessment of student creative thinking before and after exercises. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 29(1), 52-66.

Lee, B. D. (2006). A study on fashion design pedagogy for the development of creativity with emphasis on intuition. Journal of Korean Society of Clothing and Textiles, 30(3), 487–496.

Lee, S. H., & Hoffman, K. D. (2014). The" Iron Inventor": Using creative problem solving to spur student creativity. Marketing Education Review, 24(1), 69-74.

Miller, A. (1987). Cognitive styles: An integrated model. Educational Psychology, 7(4), 251-268.

Oh, K. (2017). Integrating creative problem solving into the field of fashion education. Fashion, Industry and Education, 15(1), 59-65.

Palomo-Lovinski, N., & Faerm, S. (2009). What is good design?: The shifts in fashion education of the 21st century. Design Principles and Practices: An International Journal, 3(6), 89-98.

Pedaste, M., Mäeots, M., Siiman, L. A., De Jong, T., Van Riesen, S. A., Kamp, E. T., Manoli, C. C., Zacharia, Z. C., & Tsourlidaki, E. (2015). Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educational Research Review, 14, 47-61.

Puccio, G.J., Klarman, B., Szalay, P.A. (2020). Creative problem-solving. In The palgrave encyclopedia of the possible. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Puccio, G. J., Mance, M., & Murdock, M. C. (2010). Creative leadership: Skills that drive change. Sage Publications.

Schmidt, K., & Zarestky, J. (2021). The state of fashion design pedagogy: The roles of students and instructors. Safe harbours for design research, 14th EAD Conference, 11-16.

Shephard, A. J., & Pookulangara, S. A. (2022). Teaching slow fashion: An inquiry-based pedagogical approach. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 15(1), 109-119.

Titus, P. A. (2000). Marketing and the creative problem-solving process. Journal of Marketing Education, 22(3), 225-235.